The Devil Wears Kaunda: When Relatable Style Goes Left

Kaundas were never the image of cool in Kenya; however, wearing one commanded a respected formality. In Nairobi, that is gradually changing.

Lamu. August 16, 2024.

I’ve been in Kenya for a few days shy of a month. Between my attempts at holidaying, working remotely, and noticing how expensive it is to live here, I’ve asked a few people—from waiters to tour guides and co-workers—“Do you know the Kaunda suit? What do you think of it?”

Chasing the kaunda story started in June. In the heat of the youth-led or dubbed by some as the Gen-Z #RejectFinanceBill2024 protests against over-taxation on essential everyday items, I DM-ed a friend on Instagram. “Please, what’s kaunda?” I asked. I’d just seen a cleverly designed poster with the catchphrase ‘the devil wears kaunda.’ She gave me a quick rundown, sharing pictures of what it looked like, and remarked on how witty the catchphrase was.

From infographics analysing how much government ministers spend on watches to the devil wears kaunda catchphrase - a fan-fiction-like pop-culture crossover, it was hard to miss how fashion was used to rally people around the protest.

I’ll be honest, I didn’t know what the story was going to be before I came here. All I wanted to do was tell the story of the kaunda and what it means to Kenyans following the protests. I had a laughter-filled conversation with two people about kaundas yesterday, and it felt right to start writing this.

Ibadan. October 6, 2024.

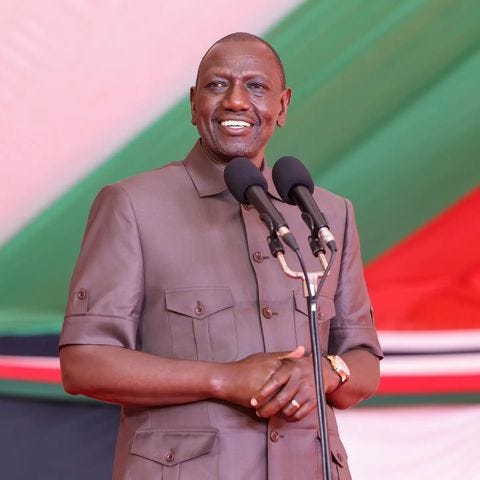

Move Over, Miranda Priestly; it’s Ruto!

For anyone reading who hasn’t watched the movie, it’s not about Prada—the brand. At the risk of spoiling it, I’ll share a synopsis similar to one you’ll find when you search for “The Devil Wears Prada” on Google.

The movie introduces us to ‘the boss’ Miranda Priestly, as everyone scampers at her arrival. The camera pans to Andrea, a young woman oblivious to the fashion world, who is about to be interviewed by the scary boss. She gets the job - an assistant to Miranda Priestly, a prominent fashion magazine editor - and has high hopes it will be a stepping stone to her big-girl career in journalism. Over time, she understood the fashion industry and came to respect it as a discipline. Despite the ridiculous requests of her boss, she exceeded expectations on the job.

In one of the movie's final scenes, Miranda tells her assistant, “Don’t be ridiculous, Andrea, everybody wants this. Everybody wants to be us.” Hearing Miranda Priestly say these words cured her of the naivety she had. She came into the world of fashion nonchalant, grew to admire it deeply and finally, at that moment, settled on being repulsed with the environment she found herself.

That scene is the most striking in the movie, and it’s no surprise it resonated with so many people. It’s a meme at this point, and if there was a hall of fame for deep-fried Tiktok sounds, it belongs there. It asks the viewer, “What [questionable things] would you do to keep a job?”

While the movie immerses viewers in the exciting world of fashion, it reminds us that fashion stories are human stories. It calls us to reflect on what we’d sacrifice at the altar of our ambitions. Seeing it referenced as a rallying call during the protests, one wonders how far Ruto will go for his presidential ambitions.

Presidential Branding

“Kaunda is like milk. No matter how rich you are, it’s the same milk you will buy as the local man will buy. You don't buy milk for 200 shillings.” [sic]

A chatty stranger at the beach in Shela told me that when I asked him why he thinks the president wears kaunda. The previous day, an older man, one I’d consider an elder, described the kaunda as his Sunday best. He excitedly whipped out his phone and showed me how he’d styled it.

The kaunda suit has many iterations; however, this slim-fitted jacket and matching pants, typically made from cotton, reads as a cross between a safari and a military jacket at first glance. For Kenyans, the story is more. While young people consider it dated, it’s still the image of a sage. Before it became the president’s wardrobe staple, it was considered formal yet traditional. It transcended and still transcends class; it wasn’t cool per se, but Kenyans respected it.

Looking through William Ruto’s official Instagram page as deputy president, there is no kaunda in sight. However, it’s pretty evident he has always used his style as a tool for communication. As vice president, he wore a formal suit and tie at official events and diplomatic engagements. Sometimes, when he was out in a remote area, his style was laidback and featured modular pieces - he got rid of the tie, his pale-coloured striped shirts were not tucked in, occasionally featuring face caps or throwing on a different-coloured jacket from his trousers.

In 2022, he campaigned under the slogan “Every Hustle Matters.” The slogan has a “we will build this nation by pulling ourselves by the bootstraps” vibe. Having worked his way up from walking to school barefooted to being a member of parliament to vice president and gunning for the highest position in the country - a hustler himself, he was the perfect vessel for his mantra. He didn’t need to use local style as a crutch. The state of the economy created an ideal environment for his pitch. After all, 4 in 5 Kenyans work in the informal economy; hustling is their daily experience.

Elections are complex, but making promises is expected. And nine months into his presidency, it is normal for anyone to start holding him accountable to his campaign promises. At this point, he could no longer claim the hustler narrative; he is the president. So, in June 2023, on a state visit to Burundi, he again fell back on clothes to communicate what his positioning couldn’t - relatability. He switched up his style and started wearing kaundas to relate with the average person - mwananchi, as someone described it to me. This was also a time he was in his “pan-African” era. On the one hand, he’s seen at the Mo Ibrahim Foundation summit arguing against African nations responding to summons by non-African institutions and the need to present a united front through the African Union while jetting across the world whenever he is summoned.

By August 2023, his style had become a point of scrutiny. In the mix of his decision-making and policies, ideas about his style were formed. People perceive the kaunda as his uniform for addressing the nation and a formal suit and tie as his international-facing outfit. In an interview on national television, his personal tailor described his new-found style as an avenue to support the local economy, promote the “African cut,” and provide more jobs.

Interestingly, in November 2023, the speaker of parliament announced the ban on kaunda suits alongside other traditional African clothes as they threatened the established parliamentary code around dressing properly. While I didn’t know what the kaunda was, if the pushback I saw on my TikTok fyp and Instagram stories is anything to go by, the ban didn’t sit well with people. Now and then, the parliament makes decisions around their code of conduct, but the passion this evoked in people reflects the perception that the ban was a move to “reserve” it for one person, making it the presidential look.

Mapping Kaunda

“…kaundas, they don’t have flamboyant colours. They stick to natural, earth tones. You don’t see a yellow kaunda unless it is a magician or a pastor. But for a respectable person, a kaunda with a short sleeve is enough.” [sic]

That is also another reference from my conversation with the chatty stranger at the beach. He described the kaunda as having a lot of African philosophy behind it.

At first glance, a picture of the kaunda didn’t register as traditional to my Nigerian eye. Even when Western forms of dress influence clothes Nigerians consider traditional, they start as campy adaptations and evolve into what we have today.

The idea that Africans own African appropriation of Western forms of dressing is one I hold dear. The difference in how Nigerians and Kenyans adopt Western dressing forms challenged my understanding of what’s both traditional and African. I struggled with reconciling that it was effortless to map this traditional suit in Kenya to its Western influence. Historically, Kenyans have always had an affinity for and agency in defining their taste in imported clothing, which precedes colonisation. As Sarah Fee describes it,

“A wave of new scholarship has emphasised that in early modern times, high style in eastern Africa came via the Indian Ocean, with millions of yards of clothes imported annually from India and, to a lesser extent, Arabia, with competition from the United States and several European countries becoming appreciable from the 1830s. All of these cloth imports were shaped by African desires, demands, and coproduction.”1

The history of the kaunda in Kenya is also shaped by local desires and demand in appreciation of a president two countries away.

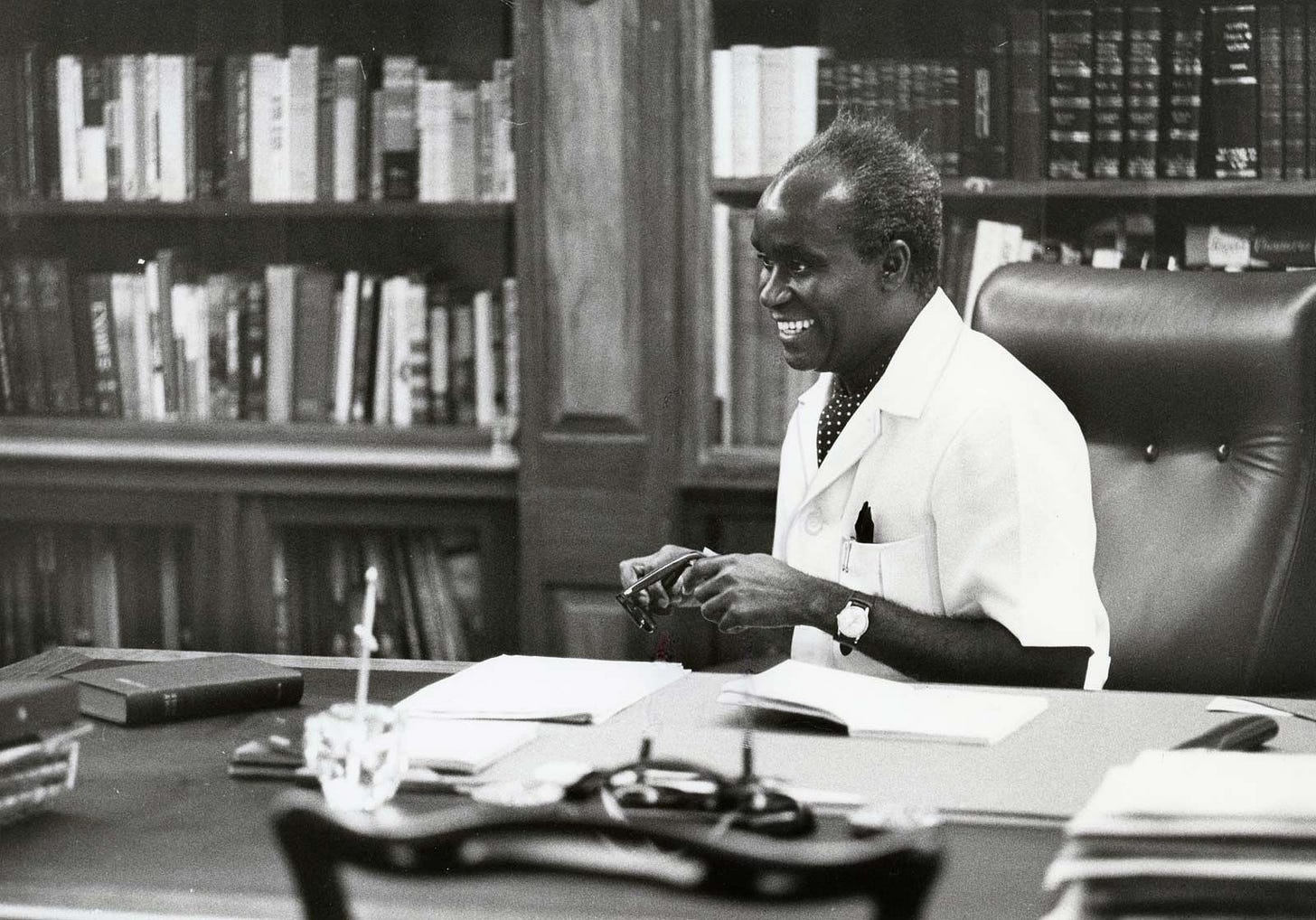

Named after Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s independence hero and post-independence president for 27 years, the kaunda is to East Africans what Prada is to fashion people. He was famous for wearing safari-style suits and matching pants, raising the kaunda’s profile to a respected level across East Africa.

In an episode of the Historians at the Movies podcast, Nancy MacDonell, fashion historian and writer of the Wall Street Journal column "Fashion with a Past", emphasised that the title of the movie “The Devil Wears Prada” is a masterful use of branding as Prada - the brand, commands an intellectual seriousness in fashion spaces. In her words,

“…the label Prada is considered a very intellectual, rigorous kind of label by fashion people. It’s a real fashion person brand. Anyone could wear Chanel, anyone could wear a Versace, but it’s a fashion person who wears Prada.”

Like many independence fighters of his time, Kenneth Kaunda was an ideas man well-versed in geopolitics and a champion for independence movements across Southern Africa. To understand his public perception, I read a paper by Dr Stephen Chan, a former International Relations lecturer at the University of Zambia. While he critiques Kaunda’s policies and economic priorities in the article, he admits that,

“There is no doubt that Kaunda is a great man. With the retirements of Senghor and Nyerere, he is easily the eminent statesman of Africa. His work as a nationalist who brought independence to Zambia, and his work as a champion of independence throughout southern Africa, guarantee his place in history.”2

Post-colonial Futures

A mix of Kaunda’s charming personality, fight for independence, commitment to championing independence for other African countries, and prolonged stay in power cemented the suit as an image of respect, power, dictatorship and sometimes, revolution. At a time of post-colonial national identity formation across the continent, the ideas he embodied were considered future-forward, influencing the perception of his style.

Zambia is a Southern African country. Looking at the map, it doesn’t share a border with Kenya. It is also 1 of 3 Southern African countries bordered by an East African country. We didn’t have the internet at the time where his [probably] flowery and evocative pan-African speeches would have made it into video edits with ambient background music. The barrier of entry to being a style influencer at the time was higher; it’s not like 2024, where creative Tiktokers would have made him cool through fan cams with K’pop music.

It’s one thing for a leader to have pan-African ideals, but it’s different for it to resonate with people [in other countries] to the point he became a style icon. For instance, Tanzania’s president declared seven days of mourning when he died, and Uganda’s opposition leader, Bobi Wine, famously wears kaunda suits. Why was he so influential? The short answer is money.

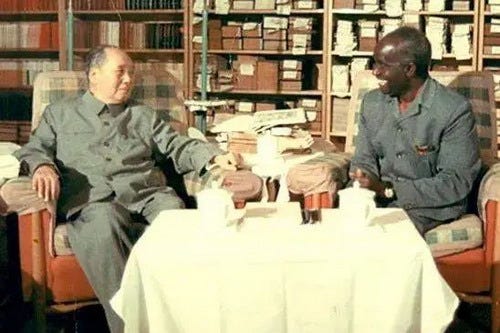

Zambia was considerably wealthy compared to neighbouring countries. Copper prices rose from 1964 - 1970, and it was the world’s third-largest producer. The country’s economic position meant the president had enough money to fund his pan-African ideals. And when the going wasn’t smooth, he forged friendships to fund this vision. For instance, in 1973, when the Rhodesia-Zambia border was closed for his role in Rhodesia's independence struggle, he took a loan from China to build a railway connecting Zambia to Tanzania - the first of its kind across the continent.3 Post-independence era African leaders of resource-rich countries faced the hard choice of funding liberation movements in struggling neighbouring countries. Some of them, like Kenneth Kaunda, ignored the consequences to national interests and funded these movements anyway.

The picture above piqued my interest because it is commonplace to see online claims that China’s Mao Zedong influenced Kaunda’s style and the eponymous suit. The Kenyan parliament speaker described it as “Mao Zedong’s coat” while announcing the ban on the kaunda. While the colours of their outfits are nearly identical, there are subtle differences in the construction - Mao’s has a wider fit with bigger collars, bigger buttons, and no lapel. It appears a lot more like a shirt than a suit. Drawing a direct link to Mao influencing Kaunda’s style isn’t accurate. Finding images of Kaunda’s style before his presidency and friendship with Mao would have provided additional clarity to understand his style influences. However, the photos and videos online are few and far between. I found a video where he wore the draped kente and assumed his friendship with Kwame Nkrumah most likely influenced that. Going off of this, one can argue that his style reflected the environment he was immersed in - his physical environment, working in the colonial government and the people he sparred with intellectually. Additionally, safari-style suits were already a style language recognised across East Africa due to colonisation, better explaining its influence across the region.

Another critical factor in becoming a style influence is consistency. The difference between today’s style influencers and those from the past is that the opportunity to have your face in front of a ready audience consistently wasn’t as democratic as it is today. Kaunda’s time in government wasn’t exactly democratic. He set up a one-party system in Zambia, creating a false sense of democracy and ensuring he was in power for almost three decades. That was more than enough time to cement the look to his name. Like many African leaders figuring out what a post-colonial national identity could look like, the line between their personal dreams and national vision was thin; a leader was the nation. As a result, the soft power the nation acquired was all personified by the leader, Kaunda.

Toppling Dominoes

Thanks to the first two years of Williams Ruto’s presidency, the suit’s lasting impression is changing—and not for good. The kaunda suit’s perception has been sustained by the actions of the people it’s been associated with—Kenneth Kaunda, church elders, and revolutionary leaders. While it nicely held contradictory ideas, the strongest impression of the suit was that of a president. So, it isn’t surprising that a president is giving it a new meaning in Kenya.

There is a lot Ruto and Kaunda’s leadership share in common—pan-African ideals, taking IMF loans, and displeasure leading to national protests. The question becomes, “Why is Ruto’s style not a national hit?” Well, he doesn’t walk the talk. Associating his time in office with a piece of clothing with such lofty ideals was always going to be a hit or miss. He missed the first cardinal rule of being a style icon - at least [pretend to] live out the ideals you project.

Well-intentioned or not, being a style influence is tough. It takes a lot to pull off a solid personal style and become a “national it-boy.” As a friend described it, “kaunda suit will be worn by local area chiefs, the clothes leaders will wear during the national holidays or [school] principals of an older generation. It’s typically associated with an older generation." [sic]

For the younger generation at the forefront of the protest, Gen Z, the affection for the kaunda is a distant memory in their psyche, and rightly so. This demographic has come of age six decades post-independence, and Ruto’s attempt at reviving it as a fashion statement is probably their most frequent interaction with it. His wardrobe, specifically the kaunda suit, is a capsule of the ill memories they associate with his government.

Like Andrea’s final disappointment in Miranda Priestly’s betrayal of their colleague, Kenyans withdrew all the good graces associated with the suit from Ruto during the protests. Interestingly, this growing disdain trends along the lines of power devolution in the nation. From my conversations with people, it is most vigorous in Nairobi, where the protests started.

Notes and Thank-yous!

I am thankful that I have friends who took the time to read this story in the middle of “adulting.” Chisom, MaryAnn, Melissah, Nicole and Neema’s feedback brought it alive.

I’m deeply grateful that people in Kenya answered my questions about the kaunda and their style. This story wouldn’t have been as expansive without their carefully considered opinions.

My productivity is usually powered by playing a song on repeat until I get tired of it. So here are the songs that were my companions at different points in the process of writing this story - “Hausapiano” by Kvng Vinci, Aqyila’s “Bloom” ft Strings From Paris, Sabrina Carpenter’s “Taste,” Chris Olsen and Sri’s cover of “Young and Beautiful,” onoola-sama’s “storyman*,” and Rema’s “March Am.” Honourable mention are the voices at Lamu House restaurant - the background noise that stayed with me as I wrote the first section of this article.

Sarah Fee (2022) ‘Finding Fashion in the Museum: (Re)Assembling a Precolonial Eastern Africa Fashion Moment’, in JoAnn McGregor, Heather Akou and Nicola Stylianou (eds) Creating African Fashion Histories, Indiana: Indiana University Press, pp. 67-69.

Stephen Chan (1987) ‘Kaunda as international casualty’, in New Zealand International Review, 12(5), pp. 6-8.

Unathoured (1974) ‘President Kaunda’s Speech (Excerpts)’, in Peking Review, 17(9), pp.10.

this is so good. as a Kenyan, I didn't have enough context for the suit to understand that he wished to reflect relatability and the politics he was trying to present.

I also love how you tied ambition as displayed in the film to Ruto's ambition.

Random take but I love how much I’ve learned about Zambia’s post-colonial politics reading this!! Fashion is embedded in everything! And the photo of Kaunda with Mao is now stuck in my head…so much to ponder over.

Also, random - Kenyan youth inspire me in the way they engage their leaders (both when they choose to show up show out and when they choose to hold still)!

Brilliant essay! Thanks for writing and sharing!